Waterline is an ongoing series of stories exploring the intersection of water, climate and food, told through the eyes of the people impacted by these issues. It is funded by a grant from the Walton Family Foundation.

Jeff Wivholm isn’t partial to mountains. He likes to be able to see the weather rolling in, something remarkably possible in the northeastern corner of Montana.

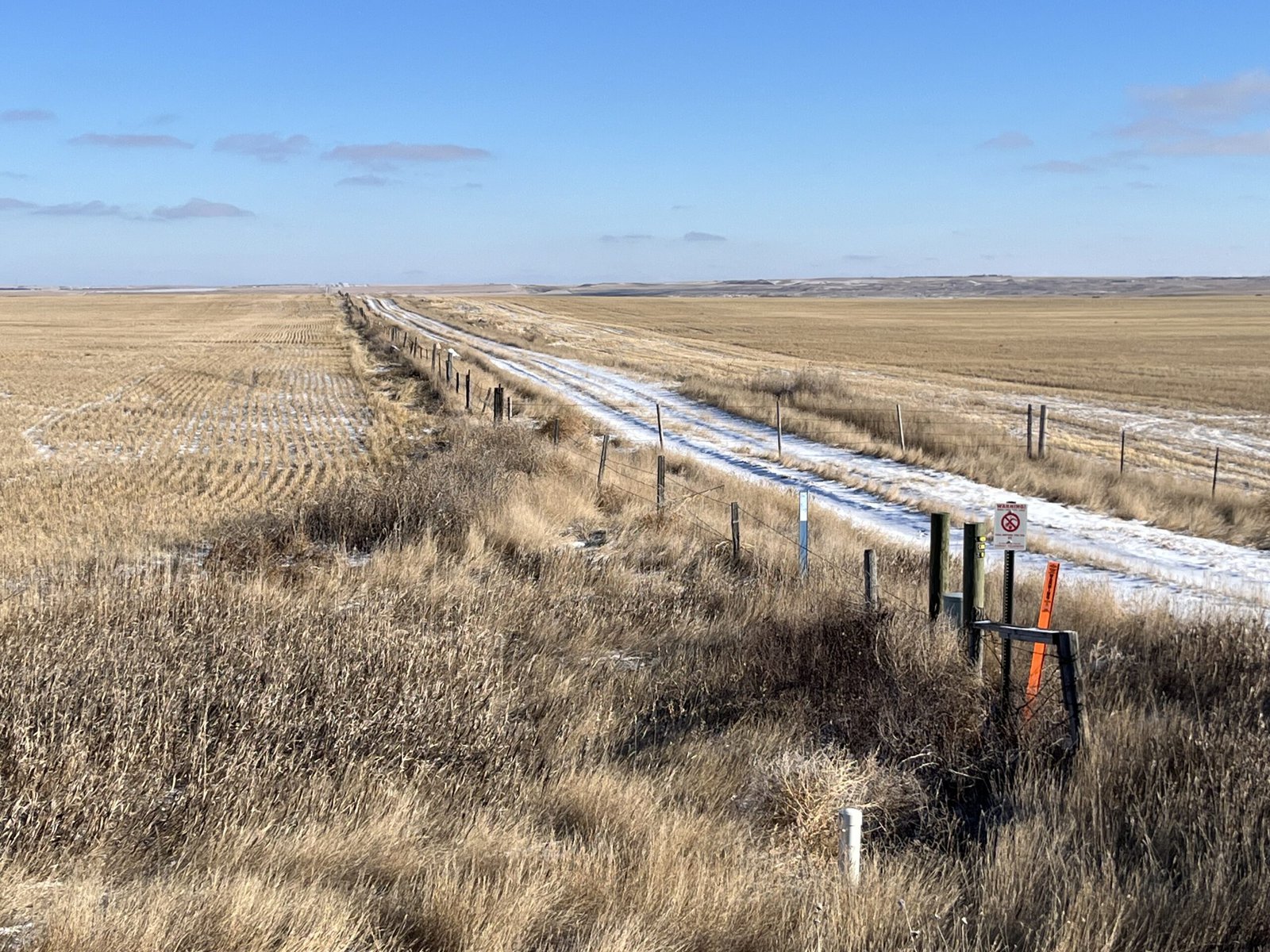

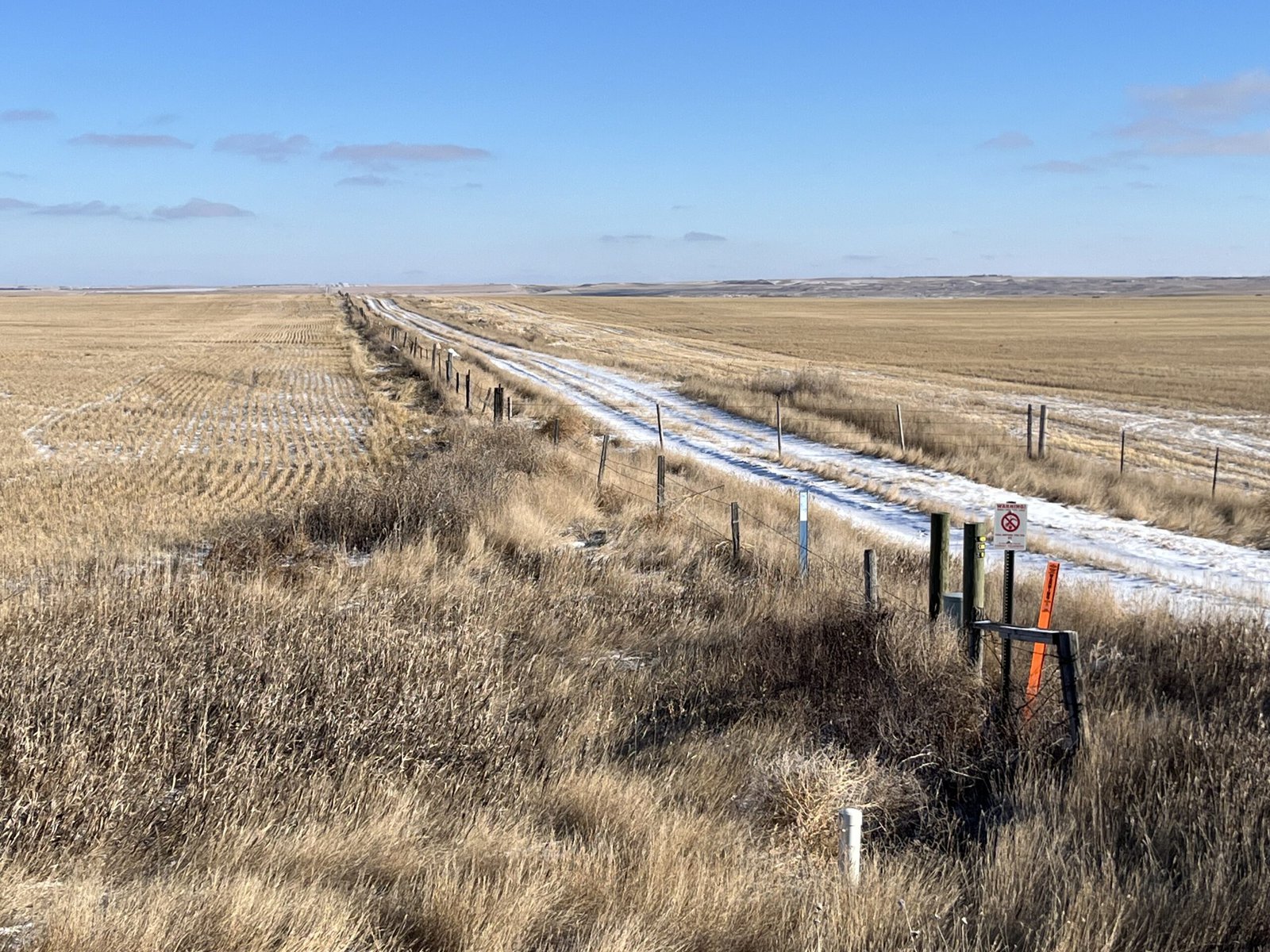

On a cold January morning, Wivholm drives the dirt roads between farms in Sheridan County, where he’s lived for all his 63 years, with practiced ease, pointing out different plots of land by who owns them. And if he doesn’t know the family name, Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District or Brooke Johns with the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge — both sitting in the backseat of his truck — can supply it.

If you look to the right there, Wivholm says, you can see the valley created by the aquifer. Maybe he can, his eyes accustomed to seeing dips and crevasses in, to an unfamiliar eye, a starkly flat landscape. He laughs and says it takes some getting used to.

That aquifer isn’t unique in Montana. There are 12 principal aquifers running like underground rivers throughout the state. But the way Sheridan County uses the water is.

Montana is in relatively good shape as far as its groundwater supply goes, something uncommon across much of the country, geologist John LaFave with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology says. State politicians initiated a groundwater study over 30 years ago after years of intense drought and fires and a lack of data.

But Sheridan County was ahead of the game: The county’s conservation district started studying its groundwater in 1978, before state monitoring began.

In 1996, the district was granted a water reservation, or water allocated for future uses, from the state, which meant it could take a certain share of water from the Clear Lake Aquifer. Because of all the data it gathered through studying its groundwater, the district developed a unique way of using and distributing that water.

What’s unusual is how intentional the collaboration was and how extensive the groundwater monitoring was and continues to be. The district does this by working with farmers, tribes and the US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) to ensure water can be used by those who need it — those who would be most affected by any degradation to the water — without negatively impacting the environment.

And it’s worked. The conservation district has been using its geologically special aquifer — a gift granted to this area by the last Ice Age — to irrigate crops, provide jobs for the region and keep agriculture dollars within the community for almost 30 years while fielding few complaints.

“To me, this represents the way groundwater development should occur,” LaFave says.

Sheridan County is extremely rural, home to about 3,500 people across its 1,706 square miles. Agriculture is a big economic driver. Bird hunting is an attraction for locals and visitors. The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, located in both Sheridan and Roosevelt Counties and managed by the USFWS, is home to many migratory bird species. It’s the largest pelican breeding ground in Montana and the third-largest in the country.

This early January morning, it’s about five degrees, but there isn’t a lot of snow on the ground. Over coffee and breakfast in Plentywood — the county seat — Yoder and Wivholm say this winter has been warmer and drier than usual.

Dry weather is not uncommon here. Droughts in the 1930s and ’80s were particularly rough. Also in the ’80s, irrigation technology was becoming more common and efficient, Wivholm says, and people began to pay more attention to the possibility of an aquifer as a way to ensure water would be available for irrigation.

“There are several nicknames for much of this property, but it was basically ‘poverty flats,’” Jon Reiten, hydrogeologist with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, says. The soil is sandy, gravelly and drought-prone. Not great for dry-land farming.

Marlowe Onstead was the first farmer in Sheridan County to use the aquifer for his pivot irrigation in 1976.

“Couldn’t raise the crop on it before,” Onstead says. After irrigation, he was able to grow alfalfa.

According to Reiten, the aquifer ranges from a mile to six miles wide and two to three hundred feet deep. The ancestral Missouri River channel, discovered in Sheridan County in 1983 as monitoring began, flowed north into Canada and east into Hudson Bay. That channel was dammed by glaciers in the last Ice Age and left behind a reservoir that was buried as glaciers melted, creating the Clear Lake Aquifer. Since the materials left behind were coarse and varied, water could move easily and be stored in great depths. A downside is that these glacial aquifers can take a long time to refill.

As drought dragged on in the ’80s, locals and county and state authorities set about figuring out the best way to distribute the aquifer’s water. Medicine Lake lies on top of some of the aquifer, and the Big Muddy Creek — where the Fort Peck Tribes require a minimum in-stream flow to promote ecosystem health — is at its southwestern border.

The Fort Peck Tribes and the USFWS were concerned about their respective water levels and how they’d be impacted by irrigation. Reiten says the USFWS was objecting to just about every water rights case that went to the state at the time, and all that litigation ended up in water court.

“That’s a lot to put on a producer, to have to go up against the federal government,” Reiten says.

Negotiations with the USFWS and the Fort Peck Tribes led to the formation of an advisory committee and the transfer of the water reservation on the aquifer from the state to the conservation district. (Per Montana water law, all water belongs to the state and individuals are required to get a water right to use it in a particular way — in this case, for irrigation.) Since then, Sheridan County Conservation District has had the authority to give water allocations from the Clear Lake Aquifer to producers without the producers having to appeal to the state.

The maximum amount of water that can be pulled from the aquifer is just over 15,000 acre feet total, a number set by the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Currently, the district is using about 10,000 acre feet. Increases are allowed as long as monitoring shows the aquifer isn’t being overly impacted by irrigation.